Study: Dad’s Smoking Habit Could Affect Future Generations

Dads who smoke could be sentencing their offspring – and the offspring of generations to come – to cognitive problems, according to a new study of mice.

When male mice were exposed to nicotine, their offspring showed signs of a mouse version of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), as well as abnormal behavior and learning impairments. [1]

Study leader Pradeep Bhide, of Florida State University, said:

“Until now, much attention has been focused on the effects of maternal nicotine exposure on their children. Not much had been known about the effects of paternal smoking on their children and grandchildren. Our study shows that paternal nicotine exposure can be deleterious for the offspring in multiple generations.”

To investigate paternal nicotine exposure’s effects on offspring, Bhide and his colleagues added nicotine to the drinking water of male mice in the lab for a total of 12 weeks. They then bred those mice with unexposed females, and mated the offspring to produce a 3rd generation.

The researchers subjected the 2nd- and 3rd-generation mice to a series of cognitive and behavioral tests to see if their father’s or grandfather’s nicotine exposure had any effect.

What did they find?

Compared to the offspring born to unexposed fathers and grandfathers, these rodents struggled more with certain learning tasks. The 2nd-generation mice also showed signs of ADHD and had lower levels of certain neurotransmitters in the brain.

The findings suggest that a father’s tobacco use may prime the brains of his children and grandchildren not only for ADHD, but for autism as well.

The authors think that nicotine causes epigenetic changes in the key genes of sperm cells. They observed epigenetic changes to key genes in the exposed mice’s sperm, including 1 that is vital to brain development. [2]

What scientists need to figure out next is how many generations can be affected by a father’s nicotine use.

Bhide said:

“It is possible that some of the epigenetic changes caused by nicotine in the sperm DNA are temporary, and go away with time, which would mean that children conceived after a certain period of abstinence from nicotine use might not be affected.

Other epigenetic changes may be permanent, and may result in deleterious effects on the offspring. More studies are needed.”

Bhide and his team wonder how smoking might have affected generation after generation

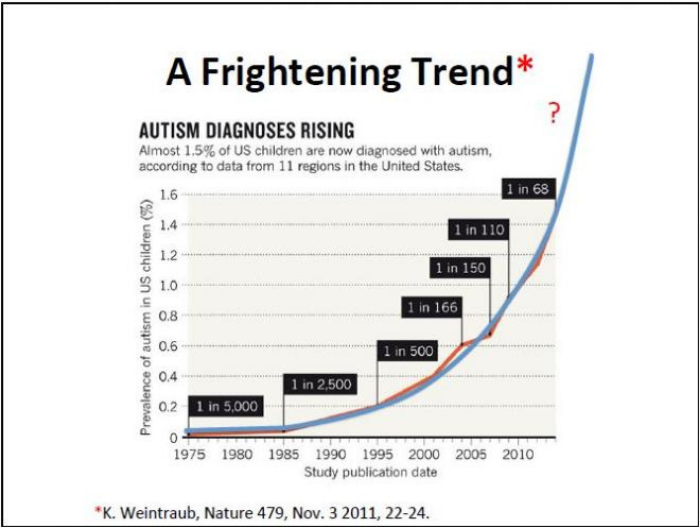

“Cigarette smoking was more common and more readily accepted by the population in the 1940’s, 50’s, and 60’s, compared to today. Could that exposure be revealing itself as a marked rise in the diagnoses of neurodevelopmental disorders such as ADHD and autism?”

Autism was first described in a scientific journal in 1943 when Johns Hopkins researcher Leo Kanner described 11 children who had an apparently rare syndrome of “extreme autistic aloneness.” These children were so young that Kanner dubbed the disorder “infantile autism.” [3]

Late onset autism (starting in the 2nd year of life) was “almost unheard of” in the 1950’s, 60’s, and 70’s. It wasn’t until 1991 that autism was listed as a separate entity under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 1975.

Today, 1 in 59 children have autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) said in April 2018 that autism diagnoses are on the rise.

The study is published in the journal PLOS Biology.

Sources:

[1] The Scientist

[2] Boston Globe