New Science Reveals How Sherpas Climb Mountains Like Everest With Relative Ease

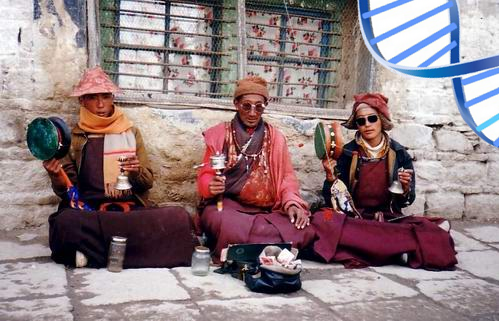

(NaturalSociety) Scientists have studied the Tibetans for decades to help them understand why this hearty group of individuals seems so well adapted to high altitudes. While modern humans have occupied every corner of the globe for more than 10,000 years, and arguably millions (with the discovery of 850,000-year-old footprints), some ethnic groups seem especially adapted to certain climates. Tibetans often scale 3000-meter-high slopes as if they were nothing, and the ‘sherpas’ that have been known to help mountain climbers, tourists, and foreigners to scale these heights are notorious. Do the Tibetans actually get help from a distant, extinct human relative?

(NaturalSociety) Scientists have studied the Tibetans for decades to help them understand why this hearty group of individuals seems so well adapted to high altitudes. While modern humans have occupied every corner of the globe for more than 10,000 years, and arguably millions (with the discovery of 850,000-year-old footprints), some ethnic groups seem especially adapted to certain climates. Tibetans often scale 3000-meter-high slopes as if they were nothing, and the ‘sherpas’ that have been known to help mountain climbers, tourists, and foreigners to scale these heights are notorious. Do the Tibetans actually get help from a distant, extinct human relative?

More than a thousand years ago, the Chinese Han dynasty, as well as Tibetans, moved into the Tibetan plateau. It turns out they have a particular gene for regulating hemoglobin from a distant human cousin that allows them to thrive in an oxygen-poor environment where many of us would perish.

It is thought that this gene was incorporated into the modern Tibetan gene pool by interbreeding with a human-like species called the Denisovans. This gene placement allowed for greater cardiovascular health, and over time, for Tibetans to adapt to a very harsh climate. A report from the University of California, Berkeley, explains this phenomenon in more detail.

Denisovans are our distant human cousins. Their DNA has been found in modern populations, namely in Tibet and China, but fossils from a Siberian cave dated at least 50,000 years ago suggest today’s Sherpa’s got a boost from ancient gene mixing. The high-altitude gene shard by Tibetans and Denisovans is not found in hardly any other population in modern society.

According to New Scientist, this means that the gene variant stayed dormant until people started moving into the Tibetan plateau. The gene then became a survival advantage, and was spread throughout the Tibetan population. This suggests how denizens of the mountain plateaus that rise 13,000 feet above sea level can survive and thrive, though the air at these climbs is thin with oxygen.

Principal author of the study, Rasmus Nielsen, UC Berkeley professor of integrative biology says:

“We have very clear evidence that this version of the gene came from Denisovans. This shows very clearly and directly that humans evolved and adapted to new environments by getting their genes from another species.”

This is the first time a gene from another species of human has been shown unequivocally to have helped modern humans adapt to their environment, he said.