Scientists Make Breakthrough in the Fight Against Superbugs

A 25-year-old Malaysian PhD student at the University of Melbourne thinks she has figured out how to kill bacteria that have stopped responding to antibiotics.

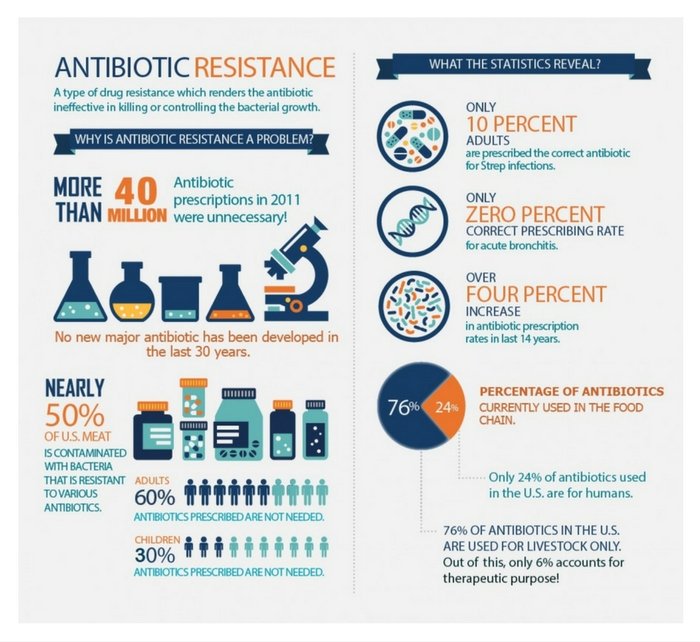

Shu Lam’s breakthrough couldn’t have come soon enough. The MCR-1 gene, which makes bacteria resistant to all antibiotics, is marching across the globe. It has been found in 4 people in the United States this year, including a toddler.

Last week, the United Nations (UN) General Assembly passed a declaration signed by multiple world leaders aimed at tackling the growing superbug crisis. These countries agreed to take immediate action, including working to limit the use of antibiotics in humans, unless absolutely necessary, and reducing the amount of antibiotics that are given to farm animals to promote growth.

Failure to take strong, immediate action could result in 10 million deaths due to superbugs by the year 2050.

The Breakthrough

Lam and her colleagues at the Melbourne University School of Engineering designed a star-shaped polymerized peptide, which is a large repeated chains of proteins. The peptide essentially tears antibiotic-resistant bacteria apart.

Said Lam:

“We’ve discovered that [the polymers] actually target the bacteria and kill it in multiple ways. One method is by physically disrupting or breaking apart the cell wall of the bacteria. This creates a lot of stress on the bacteria and causes it to start killing itself.” [1]

Lam and her team have dubbed the protein chains “SNAPPs” – structurally nanoengineered antimicrobial peptide polymers. [2]

The protein chains have been designed in star shapes with 16 or 32 arms that are approximately 10 nanometers in diameter, which are significantly larger than other antimicrobial peptides. The large size of the peptides don’t damage the healthy cells around the bacteria.

Lam’s supervisor, Professor Greg Qiao explained:

“With this polymerized peptide we are talking the difference in scale between a mouse and an elephant. The large peptide molecules can’t enter the [healthy] cells.”

The researchers tested 6 different superbugs in vitro and found that the star-shaped peptide polymer killed the bacteria, but did not damage the red-blood cells in the in vitro environment. [1]

Additionally, the team tested the polymer’s ability to fight a superbug inside of mice. They found that it killed the bacterium, Acinetobacter baumannii.

Scientists and world leaders – including the UN General Assembly – have said that pharmaceutical companies should be offered financial incentives to create new antibiotics. However, bacteria could eventually become resistant to these new drugs.

Lam’s peptide polymer is novel in that, at least according to lab studies, A. baumannii does not become resistant to it.

Lam explained:

“We found the polymers to be really good at wiping out bacterial infections. They are actually effective in treating mice infected by antibiotic-resistant bacteria. At the same time, they are quite non-toxic to the healthy cells in the body.”

The discovery offers hope and opens up a whole new avenue for fighting antimicrobial resistance, but it will take quite some time before this translates into real-world use. Researchers must examine how other types of bacteria respond to the molecules. Lam said:

“This is still at quite a primary or basic research level. What we need to do next is to look in detail at how these peptide polymers actually work.” [3]

Qiao added:

“There’s a lot of work before we go to commercialization.”

Sources:

[1] The Telegraph