First Human Injected with Controversial Genetically Modified Genes

For the first time in history, a human has been injected with genes edited using the CRISPR-Cas9 method. [1]

The experiment took place on 28 October 2016, when a team of Chinese scientists, led by oncologist Lu You at Sichuan University in Chengdu, delivered the genetically modified (GM) cells into a patient with aggressive lung cancer as part of a clinical trial at the West China Hospital in Chengdu. [2]

To protect the patient’s privacy, the details of the trial have not been released; but Lu said the trial “went smoothly.”

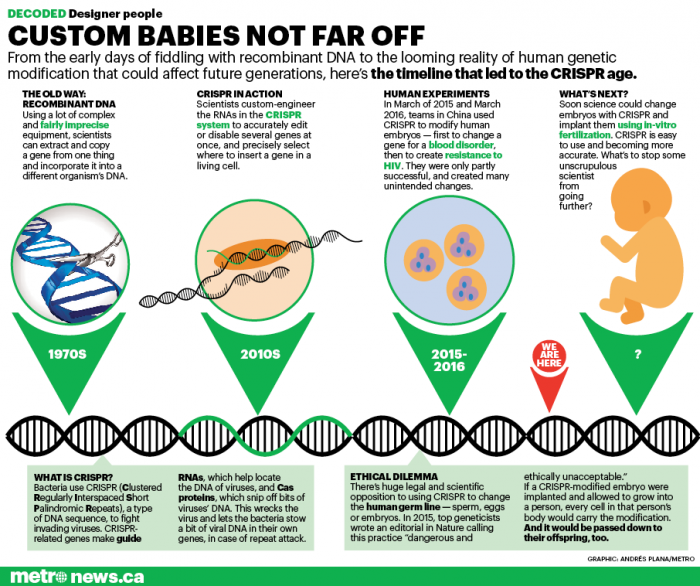

CRISPR is a tool that allows scientists to edit genomes “with unprecedented precision, efficiency, and flexibility,” according to Gizmodo. Dr. Marco Herold, laboratory head of the CRISPR facility at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research in Melbourne, Australia, explains it this way:

“The CRISPR technology relies on two components — an enzyme and a guide molecule. The guide molecule takes its enzyme to a gene which you want to modify, the enzyme cuts the gene, and then it can be repaired in many different ways. You can either change the function of the gene, take away the gene completely, or make the gene more active.”

Mad Science

The method is highly controversial. While CRISPR holds potential for new developments in medicine, agriculture, and other fields, there are deep concerns over the ethics of altering the human genome. For the Chinese trial, researchers had to gain approval from an ethics board at the West China Hospital. [1]

The cells involved in this particular trial are considered less of an ethical gray area because they won’t be passed down to offspring. But eventually, CRISPR could be used to edit embryo and sperm cells, which would usher in the age of “designer babies.” [3]

British researcher Kathy Niakin was given approval in February to edit human embryos, but only for basic research. The embryos will not be implanted, and must be destroyed after 14 days.

The Chinese experiment involved modifying the patient’s own immune cells to make them more effective at combating cancer cells, and then injecting them back into the patient.

The patient will receive a second injection; and the team plans to treat a total of 10 people, who will receive either 2, 3, or 4 injections. The primary purpose of the trial was to test the safety of the procedure. All the participants will be monitored for six months to determine whether the injections are causing serious adverse effects. The team will also be watching beyond the six-month mark to see whether the patients are benefiting from the treatment.

However, Naiyer Rizvi of Columbia University Medical Center in New York City doesn’t have much confidence that the trial will be successful in attacking the participants’ cancer. He said the process of extracting, genetically modifying, and multiplying cells is “a huge undertaking and not very scalable.” He added:

“Unless it shows a large gain in efficacy, it will be hard to justify moving forward.”

“Biomedical Sputnik”

Nature reports that the breakthrough could be a “biomedical sputnik,” referring to the Soviet Sputnik satellite that is believed to have sparked the space race between the Soviet Union and the United States. [4]

Back in June, the first U.S. human trial involving CRISPR-Cas9 was approved by a federal biosafety and ethics panel. The gene-editing method will be used to alter immune cells to attack three types of cancer. [3]

The first U.S. CRISPR trial was supposed to be conducted by Editas Medicine to try to treat a rare form of blindness called Leber congenital amaurosis. The condition affects only a few hundred people in the United States. The fact that the trial will occur in cancer patients instead suggests that CRISPR might be used against common diseases sooner than originally thought.

News of the Chinese trial could signal the beginning of an international race to implement CRISPR gene-editing techniques in clinics around the world. Carl June, who specializes in immunotherapy at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, said:

“I think this is going to trigger ‘Sputnik 2.0′, a biomedical duel on progress between China and the United States, which is important since competition usually improves the end product.” [4]

June is the scientific adviser for the impending U.S. trial, which is expected to take place in early 2017.

In March 2017, a group at Peking University in Beijing hopes to launch three clinical trials using CRISPR against bladder, prostate, and renal-cell cancers. However, those trials currently lack approval and funding.

Sources:

[1] CNBC

[2] ABC

[3] PBS

[4] Nature

Metro News

It’s going to be a disaster. Given the feedforward feedback loop of genes and the environment all the patient has to do is eat the wrong foods or go into an area where one of any number of environmental factors set off other genes that could completely wreck havoc on their health.